I’m fascinated by dry places that were once at the bottom of oceans. The Karoo is such a place, at least for a period of its ancient history it was under water. During that time rocks formed when sediments sunk to the bottom of oceans and lakes. The sediments were transported from higher ground by glaciers and rivers into the Karoo basin.

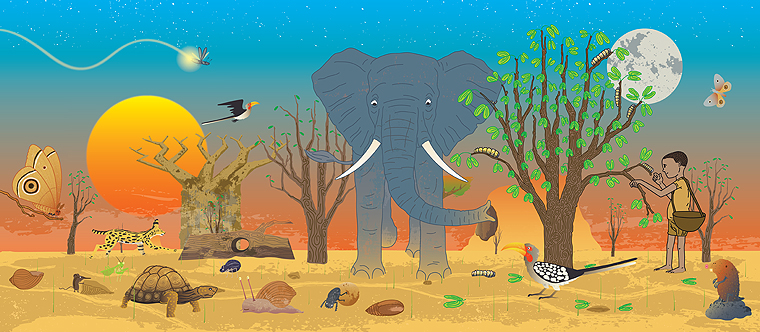

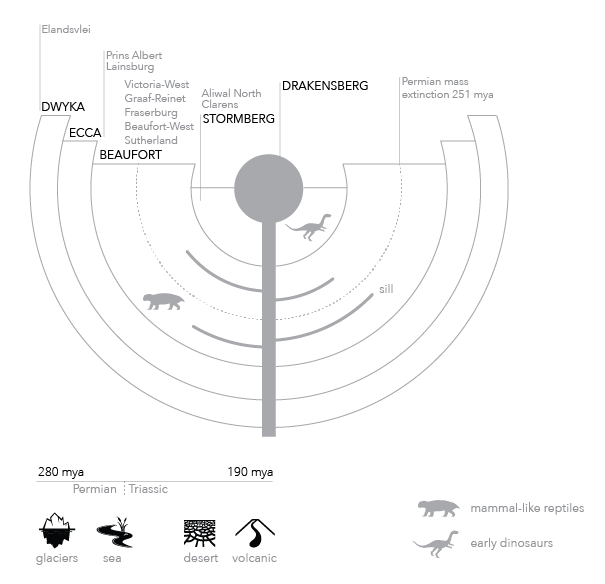

Conceptual map of the rock formations, towns, and fossils of the ancient Karoo.

But the ancient Karoo wasn’t always under water. Towards the end of a 90 million year rock forming period, the Karoo became drier, until it resembled today’s Namib desert. Then, at about 190 million years ago, lava flows covered the entire Karoo putting an end to the rock formation period. The Drakensberg mountains being the striking remnant from that event, but the characteristic Karoo Koppies are also a consequence of the upwelling lava (sills) that infiltrated older sedimentary rocks (shales) on its way to the surface. The Karoo today is the result of a 190 million year erosion process that started after the lava flows.

I like to think of the Karoo as a book, the rocks are its pages, to read the story of the Karoo you need to know what to look at, and understand what it means. But the story becomes complicated quite soon.

How to represent the story of the ancient Karoo in a simple infographic? The result of my first attempt is a conceptual map plotting rocks, fossils, and towns. I visualised the Karoo basin as a saucer consisting of 5 layers. The oldest layers are at the bottom, and crop out on the surface at the edge of the saucer. Moving towards the centre the rocks become progressively younger. This is a distortion of the actual geography, but I find it a useful model to understand the order of events, and physical structure of the Karoo.

Interesting facts cropped up during my research that I’d like to explore further: the end of a glacial period led to the formation of the Dwyka Group, and evidence of a mass extinction at the end of the Permian is visible in the rocks of the Beaufort Group.

More to explore, and more to follow.